California's Dying Sea in the Desert

By Diana Smith for The Culture-ist

Fifty miles south from the resorts of Palms Springs, on the edge of civilization, in the stillness of the California desert, there is a sea. It’s a sea that is home to thousands of skeletons. Skeletons of fish and of birds, of boats and cars, of palm trees, furniture, yacht clubs and houses. Skeletons of a community. It’s not a mirage, or another planet. The Salton Sea is a manmade mistake.

Over a century ago, the California Development Company, seeking to transform the Imperial Valley’s desert into agricultural riches, carved an irrigation canal from the Colorado River and watered the arid land. Silt, however, began to build, interfering with the canal’s water flow. In order to continue feeding the new farmland as well as investors’ pockets, engineers stemmed more canals from the banks of the Colorado. But in 1905, heavy rains caused the water to breach its canals and, instead, pour into the lowest point of the Imperial Valley, an endorheic salt basin known as the Salton Sink.

It would take nearly two years to repair the canals and get the water back on course, and in the end a monstrous land-locked body of water 35 miles long, 15 miles wide, and saltier than the ocean remained. Presumed, at first, to eventually evaporate, nutrient-rich agricultural runoff sustained the Sea’s water level and contributed to its increasing salinity.

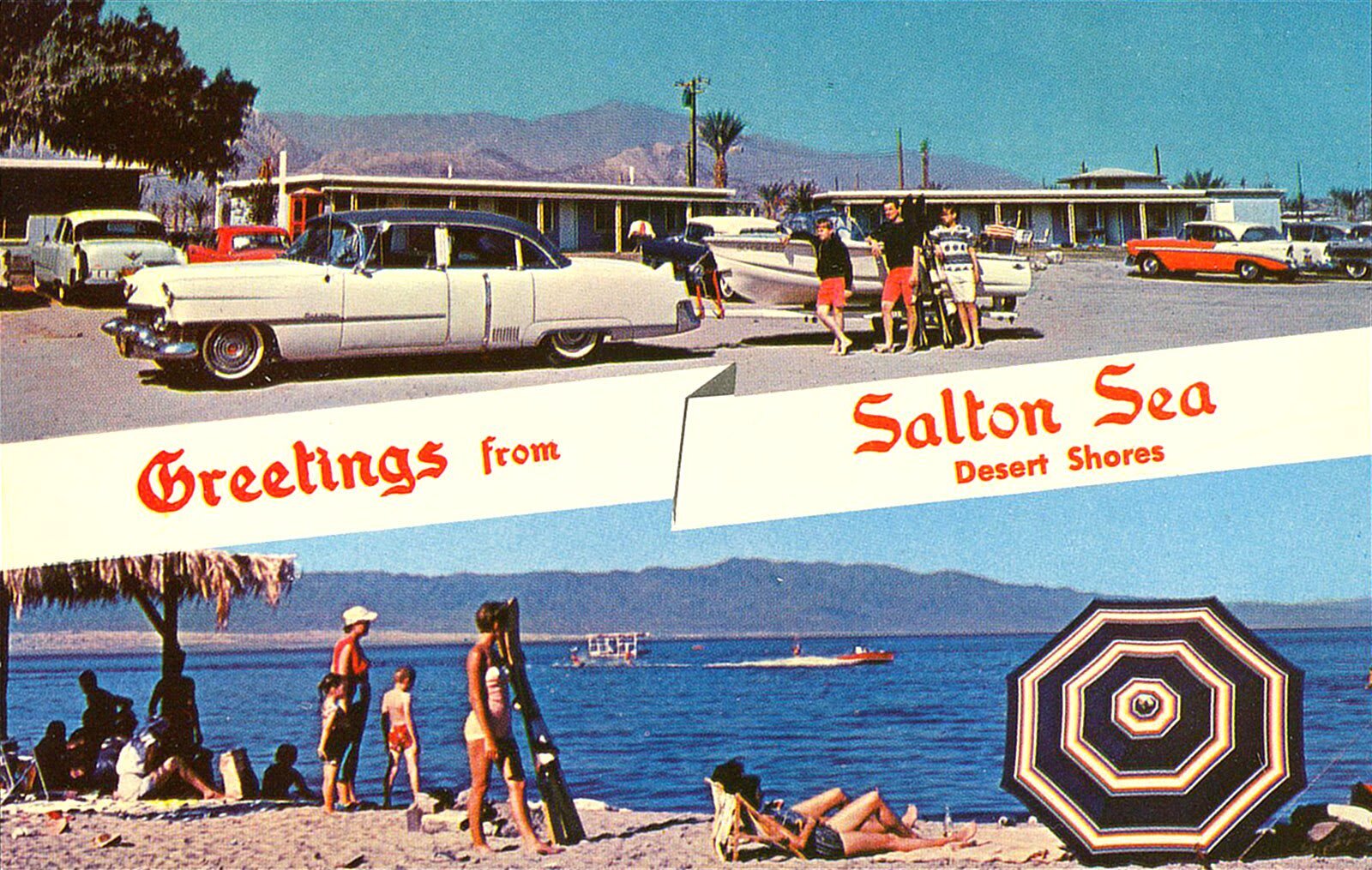

Slowly, people took notice and came to the Sea for boating and recreation. In 1950, fish were successfully transplanted into the Sea and tourism boomed. Bird wildlife flourished and yacht clubs, restaurants and resorts shot up. Families visited. Fisherman visited. Celebrities visited. It was “America’s Riviera,” racking up more tourists than Yosemite at one point. Into the ‘60s, developers, once again, saw an investment opportunity and established communities around the Sea—Bombay Beach, Desert Shores, and Salton City. Streets were appropriately given beach names like Redondo and Manhattan or given coastal names like Sea View Avenue, Shore Isle, and Shore Life. Plots were purchased. Houses and schools were constructed. It was beautiful.

But the 1970s were unkind to the Salton Sea. A few years of torrential rain and a tropical storm raised the Sea’s water level and flooded its unprotected shoreline communities. Houses, power-lines, and RVs went underwater.

Then the fish began to die.

Because of the saline, algae flourished along the Sea’s bottom. The triple-digit temperatures caused the algae to rapidly bloom and die, and the decomposition process consumed the water’s oxygen. Eventually the millions of fish began to suffocate. By the 1980s, the fishing capital of the world had turned into an underwater gas chamber.

The dying fish then became infected with botulism and poisoned the hundreds of thousand of fish-eating birds that had sought refuge at the Sea from California’s diminishing wetlands. Soon the smell of rotting corpses blanketed the area. The largest lake in California that was once hailed a miracle became a decaying oasis.

People stopped visiting. Businesses shut down. Homeowners, who could afford to do so, left their depreciated houses. Marion Penn Phillips, real estate mogul and developer of Salton City, who claimed that “you can’t buy a poor piece of California land,” abandoned his investment and fled to Oregon with a class action lawsuit by 2000 Salton City residents following closely behind.

Today, deteriorating billboards advertising land for sale haunt the Sea’s main highway. Rejected trailers lie torched and graffitied, their innards spilling out into the dust. Mailboxes stand at attention, awaiting an address or an occupant, and the corseted trunks of decapitated palms line the streets of communities where flies far outnumber people.

The Sea is also dying. In 2003, after years of droughts, a plan known as the Quantification Settlement Agreement (QSA) required conservation efforts from all agencies that sourced water from the Colorado River. The Imperial Valley for years benefitted from the largest allotment of the Colorado’s water flow, but with pressure from the federal government and a need to fund an improved and efficient irrigation system, the Imperial Irrigation District agreed to sell a portion of the Valley’s water to San Diego County. The deal enabled San Diego County to cut its unreliable water dependency from Los Angeles (which had the authority reduce San Diego’s supply by 50 percent in the event of a serious drought).

While the largest agriculture-to-urban water transfer agreement in US history is ideal for San Diego, it is less than so for the Salton Sea. Suffering from the significant decrease in agricultural runoff, it’s projected that by 2018 the Sea will shrink by 40 percent and drain completely with a few years after that.

A $9-billion plan to restore the Sea was proposed in 2007. A plan that would divide the water in two, with a sustainable recreational lake on one end and a wildlife wetland on the other. But despite all efforts, even recent requests made by President Obama to Congress for funds, the Salton Sea might not ever see close to $1 billion, let alone $9 billion.

The plan not only depends on money but water. And recently the California Supreme Court upheld the QSA, even after it had been challenged on the grounds of environmental and health issues, as the desert winds easily airborne the Sea’s exposed lakebed sediment which is toxic from salt and fertilizer. Childhood asthma rates are already three times higher in the Salton Sea’s Imperial and Coachella Valleys than in the rest of the state, as reported by National Geographic, and the quality of health is said to only worsen and spread to farther regions as the Sea recedes.

So the residents of the Salton Sea wait for a new plan. Like the Sea their community is not yet depleted. The Fish and Wildlife Service discard carcasses daily. Golf-carts continue to roam Bombay Beach. At the Salton City Christmas parade, cheerleaders fan green Mylar pom-poms alongside a marching band in gold-trimmed uniforms. To the south of the Sea, RV dwellers and drifters take over painting the late Leonard Knight’s Salvation Mountain without much disturbance. In Desert Shores, a man with the only house on his street leaves his air conditioning to tend to his yard and prune his cacti. And people in search of peace and quiet, away from the urban chatter, come to consume the stillness. For passersby, with glimmering cobalt waters and palm tree groves just off of its shores, the Salton Sea appears to be a thin slice of paradise. But for those who call it home, it’s a desperate reminder of what can happen when man tries to influence nature.

Feature image courtesy of the Salton Sea History Museum via Desert Sun